Social Determinants of Health, Intersectionality, and Models of Disability

Introduction

Social determinants of health (SDOH), intersectionality, and models of disability are key issues that can have a profound effect on the health, well-being, and health care of people with disabilities. This module addresses these issues as they relate to disability and to the ability of people with disabilities to receive health care that is at least comparable to the care provided to people without a disability. Each of these topics is addressed along with discussion of how they interact as areas in which students in the health care professions and professionals in practice can have an impact and improve the health of this population.

Social Determinants of Health

According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2025), social determinants of health are nonmedical factors that influence outcomes; such factors can have a greater effect on health outcomes than lifestyle or the health care received by individuals. SDOH are the conditions in which people are born, live, grow, learn, work, play, pray, and age. SDOH determine if individuals or populations experience health inequities, defined as unfair, unjust, and avoidable differences in health status (WHO, 2025). SDOH are relevant to all individuals, groups, and populations.

As illustrated in the figure below, SDOH can be categorized as economic stability; education; social and community context, including socioeconomic status (SES); neighborhood and the built environment; and health and health care. These, in turn, are influenced by economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies, and political systems. The five categories of SDOH reflect key issues that affect health.

Using one SDOH as an example, it is obvious that socioeconomic status influences access to a safe and healthy environment, education, meaningful employment, adequate nutrition, housing, and safe water and air. It may be less obvious that people with disabilities are at greater risk for poor health and inadequate health care compared to people without disabilities because of low SES, which can affect their access to health care, transportation, community support, employment, education, housing, communication, safe water, and nutritious food. Thus, even a single SDOH can serve as a major barrier to good health and health care for those with disability.

The term SDOH refers to nonmedical factors that influence health and includes factors that result in poor health outcomes, such as social disadvantage, risk exposure, and social inequity (Bharmal et al., 2015). These are factors that typically exist outside the delivery of health care but affect health status and the ability to obtain quality care. Another example is the lack of access to health care providers who are knowledgeable about disabilities and their effects on health, understand the effects of disability on one’s daily life, and have positive attitudes toward this population. As lack of access has a negative effect on the interactions of health care professionals with people with disabilities, health care professionals need to consider and address all SDOH that affect one’s health and well-being.

Negative attitudes on the part of health care professionals and their lack of knowledge about disability can result in their concluding that the health disparities experienced by people with disabilities are a direct result of their having a disability. Further, health care professionals may erroneously believe that people with disabilities have poor health, poor quality of life, and depression and do not contribute to society (Froehlich-Grobe et al., 2021). Health care professionals who view disability through the lens of the medical model of disability can also err in patient assessment, diagnosis, and treatment by attributing all health issues to disability, even if they are not remotely related to disability (diagnostic overshadowing). By emphasizing the importance of the environment as a key factor in disability, use of the social, biopsychosocial, or other comparable models of disability, rather than the medical model, helps health care providers avoid these issues (Froehlich-Grobe et al., 2021). The use of models other than the medical model is more likely to result in an accurate perspective of disability and its effects on the lives and health of those with disability. (See Table below.)

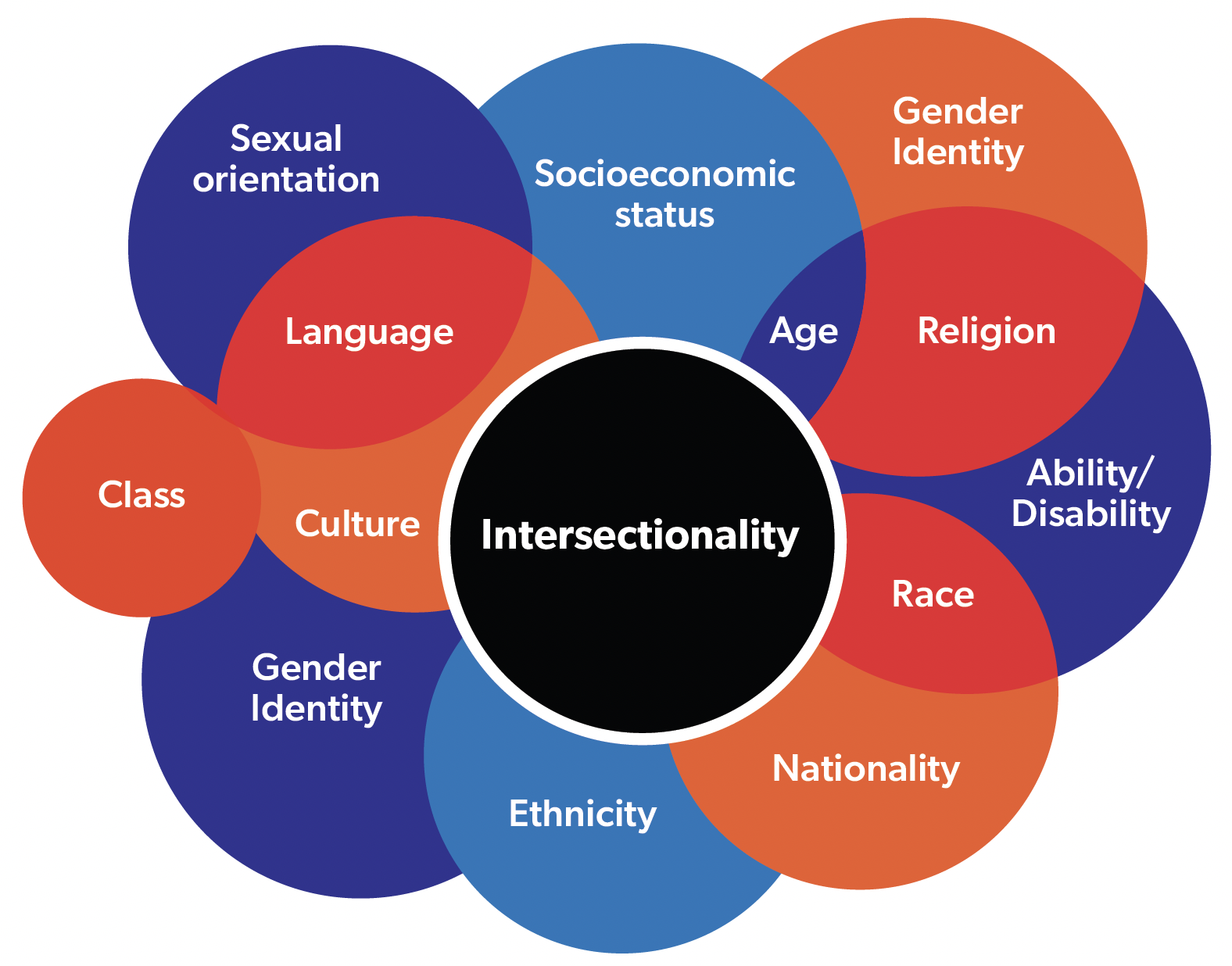

Intersectionality

The concept of intersectionality builds on the concept of social determinants of health. It describes the ways in which one’s multiple characteristics (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic class, disability, religion) interact to form an individual’s identity. These characteristics together may magnify the risk of discrimination and marginalization that an individual experiences. In other words, multiple forms of inequality reinforce one another and increase the scope of discrimination and its negative impact, leading to greater inequity and disparities. The intersection of identities (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, and the presence of a disability) can limit one’s ability to be fully included or accepted in society if others have negative assumptions about even one of these identities. When others have negative assumptions about more than one of these characteristics, the risk of discrimination or of being devalued and excluded increases.

When a person with a disability encounters a health care professional with many biases, there is greater opportunity for bias to occur because of intersectionality. If one assumes that only nondisabled people are “normal,” those with disability may be perceived as not normal or deviant, resulting in discrimination and inequity in how they are treated by others in their everyday lives and by health care professionals. For example, a child with an intellectual disability who is a person of color, from a low socioeconomic group, and whose parents are immigrants and have limited literacy skills is at greater risk for poor quality health care than a child with an intellectual disability who is White, from the middle or upper socioeconomic class, and has parents who have high literacy skills. A recent study revealed that White children with disability (identified as children with “special health care needs”) had a greater likelihood of having very good/excellent general and oral health and were less likely to experience barriers to care than a similar group of Black children (Dembo et al., 2022).

Because the intersection of multiple factors increases the risk of discrimination and poor health care, health care professionals must also consider the effects of race, ethnicity, gender identity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, and other characteristics on their interactions with individuals in their care, including those with disability. It is important to realize that one may perceive someone with a disability in a negative way without being aware of it (discussed in module on attitudes).

All of these identities have the potential to result in discrimination. Alone, each is a potential barrier to care; together, discrimination is likely to be compounded.

Models of Disability

Several models of disability have been developed to identify issues that need to be addressed to improve the lives of people with disabilities. As described above in the discussion of SDOH, use of models of disability other than the medical model is more likely to result in more accurate perspectives of disability and its effects on daily life, health, and health care. Models such as the social model and biopsychosocial model reflect the view that disability is much more than the underlying disorder or medical condition that leads to disability. Health care professionals who accept and use one of these models generally recognize that disability is far more than the disabling condition, that it includes the day-to-day experiences of the person with a disability. (See Table below.)

Further, nonmedical models of disability acknowledge that experts in disability are those persons who have lived with disability, sometimes for their entire lives, and know what health issues are important to them. Health care professionals who have been reported to know little about disability (Iezzoni et al., 2021) are rarely experts on the experiences and lives of people with disabilities. While it is important and necessary for health care professionals to know about the underlying cause of disability (e.g., disease, trauma, genetic disorder), knowledge about underlying disorders is not sufficient for providing quality health care to the large and increasing population of people with disabilities.

The following table summarizes key points of several models of disability.

Comparison of Several Models of Disability

| Medical Model | Social Model | Biopsychosocial Mode |

| Developed by health care professionals (HCP)/medical professionals; focus is on pathology or impairment due to disease, trauma, or other health condition. | Developed by disability activists in response to medical model.; | Developed by health care professionals (HCP)/medical professionals; focus is on pathology or impairment due to disease, trauma, or other health condition. Developed by disability activists in response to medical model. Developed to respond to limits of medical and social models of disability. |

| Disability viewed as problem of the individual; viewed as a deficiency or dysfunction; may result in individual with disability being blamed. | Disability viewed as socially constructed; due to physical, organizational, and negative societal barriers to be changed or eliminated. | Disability viewed as result of both biological factors and social and psychological factors; considers rather than ignores the functional impairment not addressed in the social model. |

| Disability seen as defect or abnormality. | Disability seen as difference or diversity. | Disability seen as interaction between 3 sets of factors: physical, psychological, and social or environmental factors. |

| Goal is to cure or “fix” the disability through medical interventions or by promoting change in the individual’s behavior. | Goal is freedom from discrimination with the right to same opportunities and services as others with social change as the “fix” along with elimination of negative societal perceptions. | Goal is to address both underlying physical or biological issues and social, environmental and psychological factors. |

| Based on belief that HCPs are the experts on disability. | Based on belief that people with disability are experts on disability. | Acknowledges need for HCPs to address some aspects of disability, but views those with disability as experts on how disability affects them within their psychological and social environment. |

| Views those with disabilities as “tragic”; those who “overcome” disability as inspirational or heroic. | Views those with disability as not different from others; rejects views of medical model, including view that health and disability are mutually exclusive. | Addresses health and disability from biologic, individual, social, and environmental perspectives. |

| Reinforces negative stereotyping and prejudice toward people with disabilities. | Serves as framework for UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. | Serves as basis of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). |

Summary

The intent of this module is to provide background about important issues related to disability, including the social determinants of health, intersectionality, and models of disability. These concepts provide a background necessary for health care professionals who want to make a difference in the health and health care of people with disabilities. Considering the social determinants of health and intersectionality in interaction with disability is an important step for health care professionals to identify and address factors that can interfere with quality health care for people with disabilities. Although health care professionals may not be able to remove all barriers that can have a negative impact on the health, well-being, and health care of people with disabilities, having an understanding of the factors that may come into play is an important first step in addressing those we can address.

References

Bharmal, N., Derose, K. R., Felician, M. & Weden, M. M. (2015). Understanding the upstream social determinants of health (working paper). RAND Health. www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/working_papers/WR1000/WR1096/RAND_WR1096.pdf

Dembo, R., LaFleur, J., Akobirshoev, I., Dooley, D. P., Mitra, M. (2022). Racial/ethnic health disparities among children with special health care needs in Boston, Massachusetts. Disability and Health Journal, 15(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2022.101316

Froehlich-Grobe, K., Douglas, M., Christa Ochoa, C., & Betts, A. (2021). Social determinants of health and disability. In D. J., Lollar, W. Horner-Johnson, & K. Froehlich-Grobe, Public health perspectives on disability: Science, social justice, ethics, and beyond (pp. 53-89). Springer Publishing Co.

Iezzoni, L. I., Rao, S. R., Ressalam, J., Bolcic-Jankovic, D., Agaronnik, N. D., Donelan, K., Lagu, T., & Campbell, E. G. (2021). Physicians’ perceptions of people with disability and their health care. Health Affairs, 40(2), 297-306. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01452

National Conference for Community and Justice. (n.d.). Intersectionality. https://www.nccj.org/intersectionality

Petasis, A. (2019). Discrepancies of the medical, social and biopsychosocial models of disability; A comprehensive theoretical framework. International Journal of Business Management and Technology, 3(2), 2581-3889.

World Health Organization. (2016). Health in the post-2015 development agenda: need for a social determinants of health approach. Joint statement of the UN Platform on Social Determinants of Health. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/health-in-the-post-2015-development-agenda-need-for-a-social-determinants-of-health-approach

World Health Organization. (2025), Social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

Author Information

Suzanne C. Smeltzer, EdD, RN, ANEF, FAAN

Professor Emerita and Research Professor

Bette Mariani, PhD, RN, ANEF, FAAN

Vice Dean for Academic Affairs and Professor

Colleen Meakim, MSN, RN, CHSE-A, ANEF

Director, Second Degree Track

M. Louise Fitzpatrick College of Nursing, Villanova University

© Suzanne C. Smeltzer, EdD, RN, ANEF, FAAN; Bette Mariani, PhD, RN, ANEF, FAAN; Colleen Meakim, MSN, RN, CHSE-A, ANEF; M. Louise Fitzpatrick College of Nursing, Villanova University, 2017. Revised December 5, 2023.

Users are asked to cite the source for these Villanova University developed resources as developed by the Villanova University College of Nursing and retrieved on the NLN website.